The persecution of Jews in Germany began in 1933. Eight years later, millions had become victims of mass murder. Holocaust historian Deborah E Lipstadt, described the Holocaust as “the most abominable and the most systematic act of genocide in human history.”

The scale of the slaughter perpetrated against the Jewish citizens and other ethnic minorities of Germany, in a period when that State was deemed to be the foremost example of a nation that exemplified the Enlightenment, was incomprehensible. Indeed, so heinous were the crimes against humanity in this period, it was necessary to invent a new word. In 1944 Raphael Lemkin yoked together the Greek prefix genos, meaning race or tribe and the Latin suffix cide, meaning killing. Lemkin led the campaign to have genocide recognized and codified as an international crime.

On 20 November 1945, just six months after Germany had surrendered, the words, ‘crimes against humanity’ and ‘genocide’ were spoken in a legal context. Even today, the witness statements of Holocaust survivors remain the most potent resource in the battle to preserve and disseminate the voices of those who were ‘there’. In the words espoused by the late, great Rabbi Hugo Gryn z’l, ‘When it comes to the point that the horrors of the Holocaust become unspeakable, they are also in danger of becoming unthinkable.’

On March 24 1939, a group of refugees from Central Europe held a Liberale Shabbat Service in North West London, England. After its numbers were augmented by other survivors, it became the unique Belsize Square Synagogue, a community of Jewish survivors in a foreign land. To the English they were Jews and to the British they were Germans! Above all, each and every one carried stories of displacement and degradation, yet, many carried hope and renewal despite the experiences they had endured. Every year, schools in the neighbourhood of the synagogue are invited to send their teachers and pupils to a seminar given by survivors on the subject of the Holocaust and the post traumatic effect it has to this day on the presenters and their descendants as well as the parallels in the treatment of race-based hatred. Teachers and pupils are all given the opportunity for Q&A sessions with the survivors. Sadly, as the years pass, so do survivors, and the precious testimony they carry.

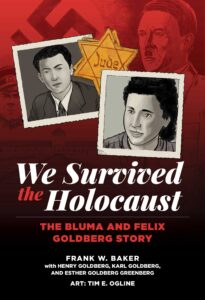

In conclusion, the graphic novel is the ideal means for carrying forward ‘voices’ beyond the life-range of the testimony-holders, they are the perfect format for time-capsules, in this case, both for teachers and pupils.

The reader could quickly detect what can be a litany of false memories. In this case, there is never a sense that the text has been manipulated, rather, it fondly brings to our eyes and to our hearts, honest testimony.

Details such as clothing, buildings, life-style information, all are faithfully reproduced in these little images, be it depictions of concentration and death camps or life in the USA after the catastrophe and the sound of happy people with love, life and hope stretching before them. We can hear the very timbre of their voices as we seamlessly are drawn into each of the images. Bluma and Felix Goldberg share with us the Nazi milieu with no hint of prurience or sensationalism. Like good testimony-givers, they just tell us how it was. Nor is the happy ending of having survived over-sentimentalised. They give us images of people who are survivors and have survived and have done so, without the debilitation of survivor-guilt.